GEORGIA and Verdana, Lucida and (to a lesser extent) Arial and Times New Roman have served us well. For fifteen years, these cross-platform default fonts have been faithful stewards of our desire to read, write, design, and publish web pages. Yet we designers have always wanted more. As far back as 1994, we hoped for the day when we could brand our layouts as magazine and poster designers do, by setting our pages in Franklin or Garamond, our headlines in Futura or Rosewood. And since 1998, CSS2 has provided a standard way to embed any typeface, not just the fab five, on a web page.

In August, 2007, CSS co-creator and Opera Software CTO Håkon Wium Lie wrote CSS At Ten, reminding us that CSS provided a mechanism by which actual font files could be linked to and retrieved from the web. Soon after the article was published, “web fonts” discussions started popping up at interactive design festivals and my friend Jeffrey Veen got the idea for a product that would get web fonts happening without running afoul of inconsistent browser support, multiple format hangups, or type designer licensing agreements and piracy concerns.

Speeding up design acceptance

While browser improvements and web standards alone provided multiple partial solutions, Typekit offered a complete solution that just worked. And the people behind Typekit (including Bryan Mason and Jason Santa Maria) did everything right: they reached out to the type design, graphic design, and standards-based web design communities; they worked with vendor after vendor to offer as many fonts as possible; they spoke everywhere, marketing their venture one lecture and even one designer at a time.

Typekit excited the web design community about type and proved that licensing and hosting web type was a viable business, providing options and convenience for designers and their clients, while bringing new revenue to type designers and protecting their intellectual property.

Typekit is the tipping point

Publicly and truly, I support Typekit because it is getting us to the world of web fonts faster. We could wait indefinitely for type vendors to agree to industry-standard licensing terms and font formats. We could wait far longer for IE, Firefox, Safari, Chrome, Opera, Opera Mini, Mobile Safari, and the rest to support the same font formats. (Currently Firefox supports WOFF and TrueType, Safari and Chrome support TrueType, MobileSafari supports SVG, IE supports EOT, and on, and on.)

But with Typekit, we don’t have to bother our pretty little heads worrying about these inconsistencies, and we don’t have to sit on the sidelines, waiting for all font makers and all browser makers to support a single standard format.

Platforms and performance

Typekit works, and that helps web designers and type designers take “web fonts” seriously. Typekit’s success is even helping to make web designers and type designers more aware of platform problems that can make fonts hideous on various platforms. Georgia was designed for the screen. Garamond was not. Moreover, platforms vary the way they hint fonts (Apple throws out hinting altogether, Microsoft over-hints) and the way they render them (from purely pixellated to at least three varieties of sub-pixel anti-aliasing), making a font’s appearance on a given user’s system hard to predict.

If not for Typekit, we might have had to wait years for most or all type designers to license web fonts. Only then would we have discovered that body text set in anything other than Georgia and Verdana pretty much blows on many Windows OS, browser, and monitor combinations.

Thanks to Typekit, we all know about the problem, and type designers are re-hinting their fonts, and in some cases redesigning them for the screen.

For all this I and all of us can be grateful to Typekit.

They also understand that designers will only use “web fonts” if they have access to the fonts they need. Just as a huge selection enabled iTunes to dominate online music, Typekit’s makers know their service must offer pretty much every good typeface out there—and they are working on it.

Renting versus “owning”

All this said in Typekit’s favor, I have mixed feelings about their product because I’d rather buy a web-licensed font than rent it—and Typekit’s success at establishing the viability of a rental model means that individual type foundries will also rent their fonts—and those who succeed at renting their fonts to web designers may not be inclined to sell.

Of course you never really own the fonts you buy—you simply license their use. So the analogy of owning versus renting doesn’t exactly hold true. But a one-time font purchase as a line item in a design budget is easier to explain and sell to a client than an ongoing rental charge.

Web Standards and @font-face

My other qualm has to do with a preference for pure web standards over product-assisted web standards. I don’t know if my preference is ideological or just the way my mind works (or fails to). But, given my druthers, I’d rather see millions of websites using standard @font-face to link to self-hosted web-licensed fonts than see that same number of fonts using a service—even a brilliant service created by friends for whom I wish continued, deserved, great success. It must be a quirk of mind; there’s no other logical explanation for this preference.

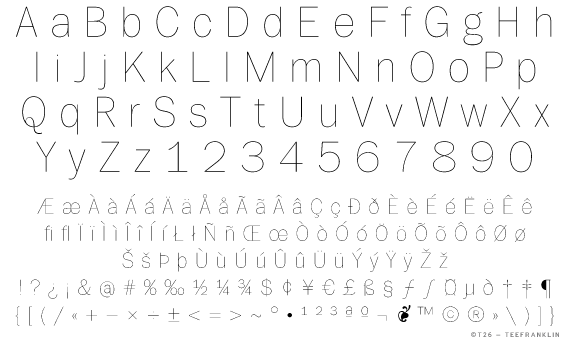

For those who share this bias, possess the properly licensed fonts, and don’t mind using FTP and writing a little code, the CSS @Font-Face Generator by Font Squirrel provides an exceptionally easy way to automatically generate the font formats necessary to take all browsers (including mobile) into account—complete with automated Cufón backup and your choice of best-practice @font-face code strings.

See also FontSpring.

Read more